Recently, I came across this question which someone claimed to lead to a fallacy.

If the covid vaccine has 95% efficacy, then if we sample 100 people,

what is the probability that 95 of them develop immunity?

The answer.

P(95 immune, 5 not immune) = \({}^{100}C_{95} \times (0.95)^{95} \times (0.05)^5 = 0.18 = 18\%\)

The answer to this question seems fallacious, but it is not.

But why 18% and not 95%. Aren’t we supposed to get 95% probability that 95 people develop immunity from the covid vaccine?

There is no fallacy about the population immunity being 95% and sample immunity being 18%. The probability that exactly 95 out of 100 gets immunity is 18%. What we really want to know is what is the probability that at least 95 out of 100 develops immunity.

All possible combinations of

(# of immune, # of non-immune) under the constraint that # of immune + # of non-immune = 100

are allowed to occur with a finite probability. Not all those probabilities are equal. Some are

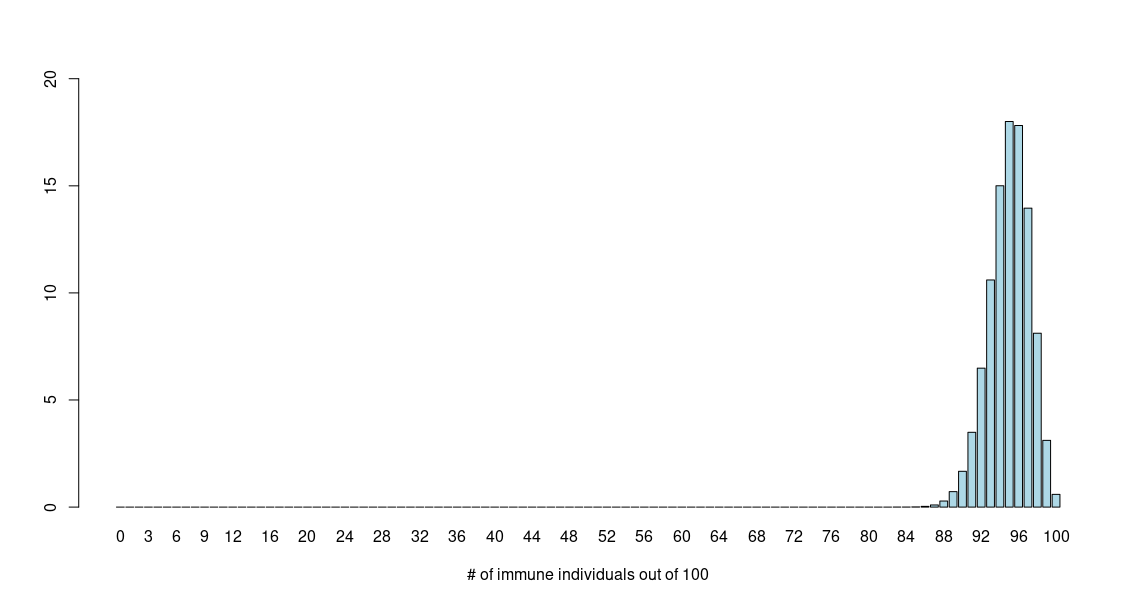

more probable, and some are less probable. Plotting the probabilities produces the following graph.

From the plot we see that the probability peaks around 95 and then trails off in either direction. So, although the values sharply peak at 95, the probability of getting 94 immune individuals (out of 100) is similar to that of getting 95 or 96. In fact, a series of values which are not 95 have finite probabilities. The correct question to ask would be

If the covid vaccine has 95% efficacy, then if we sample 100 people,

what is the expected number of immune individuals?

The answer: 95. While the probability for 95 immune individuals from a group of 100 is 18%, the expected value (the expected value is the mean value) is \(\Sigma ( n(x) p(x) ) = 95\).